Last month, I spent a fabulous few days in the US, first with school leaders in Frederick County – a district trailblazing cognitive science-informed practice – then on to the Festival of Education in Potomac, Maryland, an uber-cool celebration of teaching, learning and coaching offering inspiring keynotes and a range of workshop sessions.

It was a week of great discussion with some super-knowledgeable folk. One particular conversation, just before my session on Coaching Mental Models at the Festival, was about what can and what can’t be considered ‘coaching’. Incidentally, this topic cropped up in another session too, happening simultaneously so I wasn’t able to attend, but I understand that the speaker expressed some pretty damning views on emerging models of coaching in the US and UK.

The impression I got from both speakers is that coaching is only coaching when it is purely facilitative, and anything else, such as the coach sharing ideas, advocating useful solutions or actions, even guided modelling and rehearsal, is absolutely not coaching. I have a really hard time with this. I don’t doubt that facilitative coaching can be a highly effective approach, but it is not the only valid form of coaching, and the idea that coaching must be 100% facilitative to be considered true coaching is far too restrictive for my liking.

It’s absolutely obvious to me that coaching exists in many different forms. Life coaching, health coaching, instructional coaching, sports coaching – so much variety exists across different domains that it’s almost churlish (and unhelpful) to be so semantically territorial, to double down on this rather weird form of linguistic or conceptual gatekeeping.

What matters more is what we actually do as coaches to be useful to the teachers that we work with. To be helpful. To empower teachers to make sense of and solve the everyday challenges of the classroom. To support them to build and refine their mental models of teaching so that every class they teach – forever – feels the benefit. And to do this, we need to be flexible and responsive in our approach, particularly against the backdrop of busy schools and time-poor teachers.

I think a great starting point here is Jim Knight’s coaching continuum. Not because I think that coaching must be exclusively dialogic… I don’t (and I might be wrong, but I don’t think that Jim does either). But nor do I think that it must be wholly facilitative, or wholly directive… I don’t. What I really love about Knight’s model is that it prompts responsiveness. The starting point is always dialogic – if it wasn’t thus then we’d never know what was needed of us as coaches. But dialogue is interactive by nature, a back-and-forth exchange, where responses build on or react to what has previously been unveiled.

So, if what is said by the teacher demonstrates a secure understanding of pedagogical purpose, situation awareness and response, then my response as a coach needs to be facilitative – that’s how I can be helpful. If what is said by the teacher demonstrates an uncertain understanding of these things, then I need to be more directive – that’s how I can be helpful.

Let’s pause on that for a moment. What if the teacher’s sense of purpose, assessment and response is spot on, but I refuse to budge from my dialogic-directive position? Well, I likely end up discussing things that have already been uncovered, or worse, offering insights that are neither welcome or needed. Either way, I stop being helpful to the teacher.

What if the teacher is really struggling to make sense of their current reality, or isn’t able to form insights, or a self-made solution? Do I let them flounder, feeling unsuccessful and inadequate, as I try to tease from them an answer that they simply don’t possess? If I refuse to budge from my dialogic – facilitative position – if I withhold my insight and expertise – I stop being helpful.

I think the key to great coaching is to be responsive – to slide along Knight’s continuum in order to be as helpful to the teacher as possible.

So far, I’ve suggested that:

- Coaching exists in many different forms. Semantic territoriality is unhelpful at best, and harmful at worst.

- The number one goal of a coach is to be helpful to the teacher.

- Coaches shouldn’t adopt a fixed disposition – they should be responsive to the needs of the teacher.

So, where does this leave us? I’ve written a lot here about how coaching needs to be helpful to teachers, and how coaches need to respond to the needs of the teachers that they work with. But what does that look like in practice – in real schools, many of whom are operating in massively challenging circumstances? And I make no pretence here… these are schools where coaching isn’t a simply a luxury, but a necessity. Rural, South Wales ex-mining communities, where I taught for 16 years, post-industrial towns in the North of England, coastal towns suffering significant economical decline, inner-city deprived areas, steelworking and shipbuilding towns… these are home to some of the most challenging classrooms. Teachers here play such a crucial role in the life chances of their students; they need and deserve all the help they can get. And they need more than talk. When I talk about coaching, it’s for these teachers, in these schools. I think they need:

To feel like they can succeed. To feel like the challenges they face are surmountable. To feel like they’ve got support. To feel like professional development is for them, and for their students.

To make sense of what is happening in their classrooms. To understand the challenges that their students face. Time and space to think deeply about their practice. To formulate goals and make predictions.

To have a plan of action. To have hope in a realistic solution. To develop the technical repertoire to meet the demands of the classroom. Support to enact their thinking in the classroom.

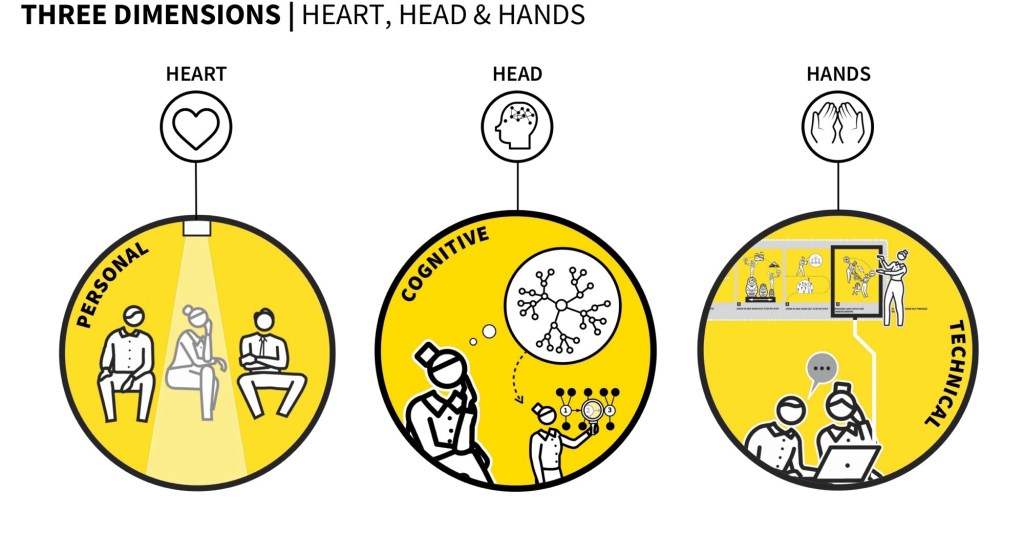

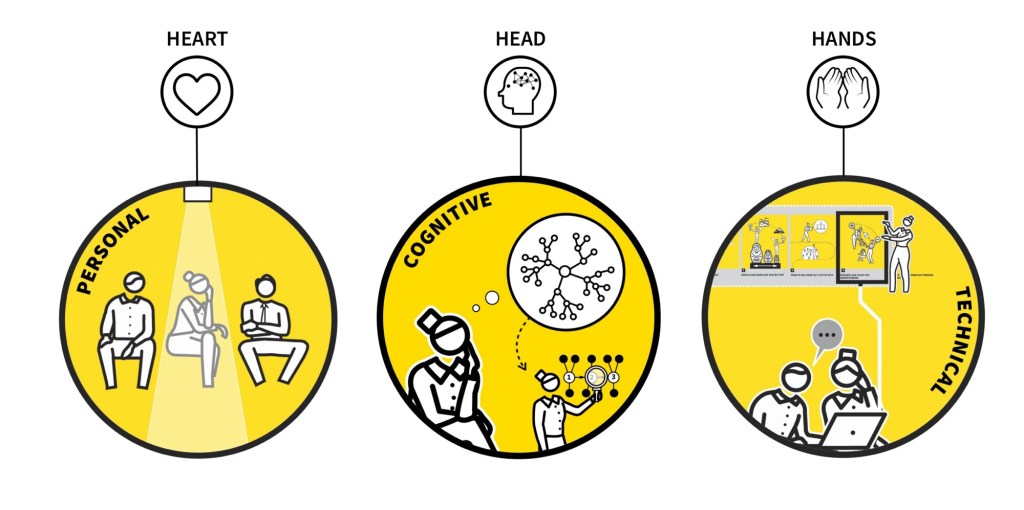

As coaches, we need to provide these things. That’s why I think it’s important that the support that we offer to teachers is flexible, and should, I’d suggest, aim to support the teacher in three core domains: personal, cognitive and technical.

To recap:

- Whilst coaching might be a luxury to some schools, it’s a necessity to others.

- Teachers, especially those working in the most challenging circumstances, need to be supported in three core domains: personal, cognitive and technical.

The Personal Domain

Coaching has to be useful to the teacher as an individual. This means that the thing they are working on needs to be useful to them and the students in their classoom. The goal has to be relevant to their practice. It always baffles me when school leaders ‘gift’ a goal to teachers and then wonder why it doesn’t land. Why would anybody really work on anything that wasn’t worth their while? As in, why would a teacher invest in the effortful process of habit change if they didn’t recognise the need to change in the first place, or if they didn’t genuinely believe that the thing they’re working on would make a difference to either them or their students?

Another important element at play here are the terms of engagement. What are the conditions under which the coaching is taking place? When coaching is a remedial process – when it is targeted or ‘done to’ – it just doesn’t work. If a teacher feels like they’re being coached because they’re not good enough, or they’re being coached on other peoples’ problems, why would they invest in changing their practice?

I think Knight’s Partnership Principles are super-useful in helping us nail coaching in the personal domain: Equality, Choice, Voice, Dialogue, Reflection, Praxis & Reciprocity.

These principles help establish a coaching environment based on trust and mutual respect, ultimately aimed at improving teaching practices collaboratively. Under these conditions, teachers are more likely to recognise the coaching process as useful to them, and are likely to be more motivated to invest in developing their practice.

The Cognitive Domain

Teachers need time and space to think deeply about their practice. They need to make sense of what they are seeing in their classrooms, where their students might be struggling, or where they can improve. The cognitive domain refers to how a teacher processes information, thinks through problems, makes predictions and plans changes and solutions. It involves thinking strategies, mental models, and pedagogical frameworks that guide decision-making. Our thoughts are intertwined with our actions, so in order to change our practice, we need to change our understanding. Coaches can be useful in the cognitive domain by helping teachers to mediate their thinking, build situation awareness, explore and exchange insights, and support their understanding of learning theories, subject knowledge, and teaching techniques.

The Technical Domain

An important part of a teacher’s role is technical – teaching is to no small degree an instructional domain. This means that teachers with a broad pedagogical repertoire are better equipped to respond in the moment to the challenges of the classroom. Coaching is useful to teachers when it supports them to develop teaching techniques and – importantly – to build intentionality around when and how they can be used in the classroom. In my work, this is where the WalkThrus toolkit is super-useful… a common language around pedagogy that helps teachers to organise their thinking. A playbook helps us to talk about teaching and learning in a cohesive and productive way, enables us to support teachers with high quality training and modelling, and gives teachers real, practical solutions to classroom situations.

I get the feeling that sometimes it’s the technical element of coaching that upsets the purists. But I work with so many teachers who need, by their own recognition, practical tools to help them in the classroom. Teachers need the tools to enact their ideas.

So…

- For coaching to be effective, it has to be personal to the teacher. They have to recognise the problem and attach value to the solution.

- Coaching should be cognitive. It should give teachers time and space to think deeply about their practice.

- Coaching should be technical, too. It should help teachers to develop teaching techniques that can be enacted intentionally in the classroom.

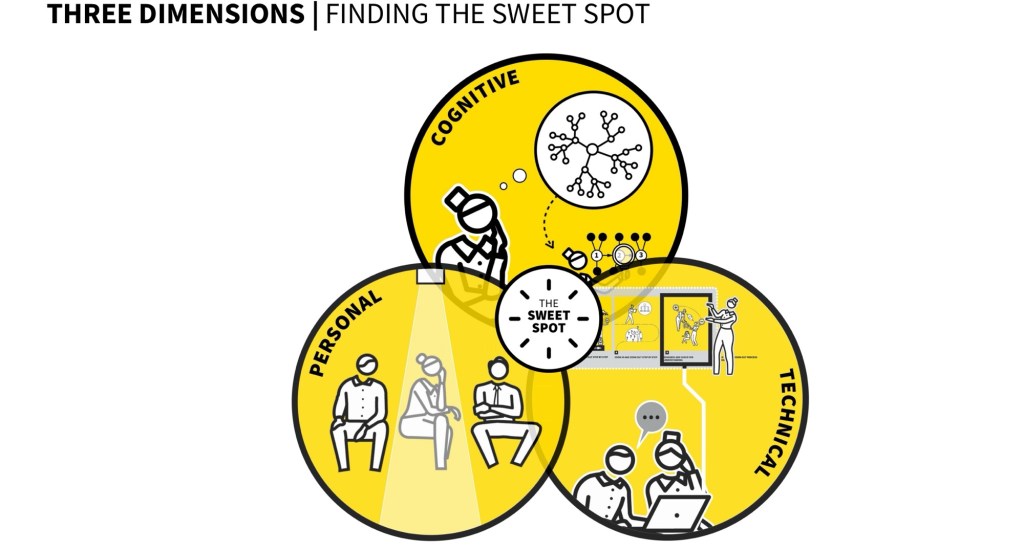

The Sweet Spot: Where Cognitive, Technical, and Personal Domains Intersect

When the personal, cognitive and technical elements are all present and working in together, we’re more likely to see teachers who are personally motivated to invest in their practice because they are professionalised and respected as partners in the coaching process. They are given time and space to make sense of their thoughts about their classroom, to explore their mental models of teaching, to make predictions and simulate scenarios. They are able to lean into a broad repertoire of teaching techniques, that they can use purposefully and intentionally in the classroom.

I’d suggest that this “sweet spot” represents the most effective coaching, where each domain reinforces the others.

I think this model is useful in explaining different approaches to coaching. Different models prioritise or sideline different domains. In my opinion, this almost always results in less effective support for teachers. In fact, I think it’s probably why many teachers are switched off to coaching in the first place. Let’s have a quick look at what happens when each of these elements is missing.

Missing the Personal Domain…

When coaching neglects the personal domain, it risks a scenario in which the teacher never really buys in to the intended change. Unless teachers recognise the change that needs to be made in their practice, why would they commit to it? For coaching to be successful, the teacher needs to feel that the process is for them, that they are working in something useful and valuable, and that they are respected as a professional. Without this, at best we’ll have teachers who are compliant – it likely for the wrong reasons. In my work with coaches and leaders, I always come back to the 99% problem – teachers are on their own for 99% of the time, often behind closed doors. The reality is that they’re only working on things that they perceive to be helpful..

Missing the Cognitive Domain…

Teachers need time to figure out how and why a particular challenge is occurring, and why their chosen solution might be useful. They need time and space to explore options, predict outcomes, and simulate scenarios. They need time and support to adapt routines into the context of their own classrooms, to plan their roll outs and get a sense of what the solution might look like in practice. Without this domain in play, teachers are far more likely to experience the problem of enactment – the challenge of really knowing how, if, where and when a particular idea might be useful.

Missing the Technical Domain…

If we fail to support teachers to develop their technical craft, we run the risk of leaving them floundering in the face of the challenges that have surfaced. We might have a situation where the teacher recognises a problem, understands why it is happening and designs the change that they want to see, but doesn’t have the tools to see it through. Supporting teachers to build a broad pedagogical repertoire should be a core aim of coaching.

So, there it is. Coaching teachers is complicated… too complicated to pigeonhole into any single domain. And it’s important… too important to get territorial over what it might or might not be. Call it what you want, but the number one goal of coaching is to be as useful as possible. In my work, the three domains explored in this post seem to make sense.

Thanks for reading, and I hope that you found something useful to take away!

Matt

Leave a comment